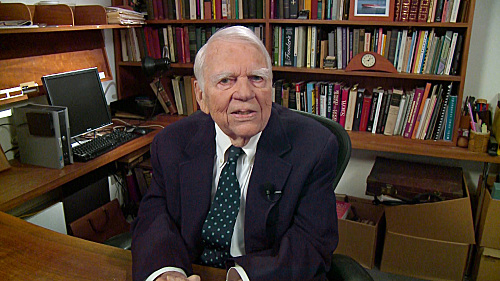

Andrew A. Rooney said he’d be working until he died. He just about did it with a month to spare. At age 92 he retired from CBS as the only personality with a weekly segment on 60 Minutes.

He came from 70 years of writing that began in WW2. Rooney was a declared pacifist and assigned as a reporter/writer for The Stars and Stripes where he became the eyewitness to several historical events including the liberation of the first concentration camps. Rooney says the wartime experience made him ashamed of his anti-war views and forced his rethinking of the justified wars concept.

Four years later he wrote for Arthur Godfrey at CBS. Three years later the show was number one in television. Rooney moved to Garry Moore‘s program where it soon became a hit series with the help of his writing.

Rooney continued to work for various projects at CBS including The Twentieth Century with Walter Cronkite and his special Essay series with Harry Reasoner through 1968 where he won his first of three Emmys (for Black History: Lost, Stolen, or Strayed). But he left CBS after a dispute over his script on An Essay of War and went to PBS where he read that CBS-kill piece on-air and the public saw his face-performance for the first time. He ended up winning a third Writers Guild Award for the report.

Two years later CBS happily welcomed Rooney back with several assignments including Mr. Rooney Goes to Washington (that won a Peabody Award) and threw him in as a summer placement for the segment-ending 60 Minutes program. By the start of 1979 Rooney was the permanent tail of the show.

In 1990 Rooney made a television comment, saying “too much alcohol, too much food, drugs, homosexual unions, cigarettes (sic)all known to lead to premature death.” Against CBS orders he wrote a letter to gay organizations explaining his offending sentence. Rooney then did a phone interview with a reporter for a gay-issues newspaper where the interviewer later said that Rooney made a racist statement.

Although the reporter hadn’t recorded the interview, the accusation got Rooney suspended by former CBS News President David Burke.

While out of work, Rooney lined up prominent civil rights legends as witness to his lifelong support for African-American rights.

While I and Mari owned and ran a newspaper in 1990, Rooney was one of our syndicated columnists. I wrote an essay describing how Private Rooney was the only White in a sit-in with Black soldiers against U.S. Army segregation 20 years before it was fashionable.

Four weeks later CBS caved (after 60 Minutes fell 20% in viewers) and Rooney said on his return that “There was never a writer who didn’t hope that in some small way he was doing good with the words he put down on paper and, while I know it’s presumptuous, I’ve always had in my mind that I was doing some little bit of good. Now, I was to be known for having done, not good, but bad. I’d be known for the rest of my life as a racist bigot and as someone who had made life a little more difficult for homosexuals. I felt terrible about that and I’ve learned a lot.”

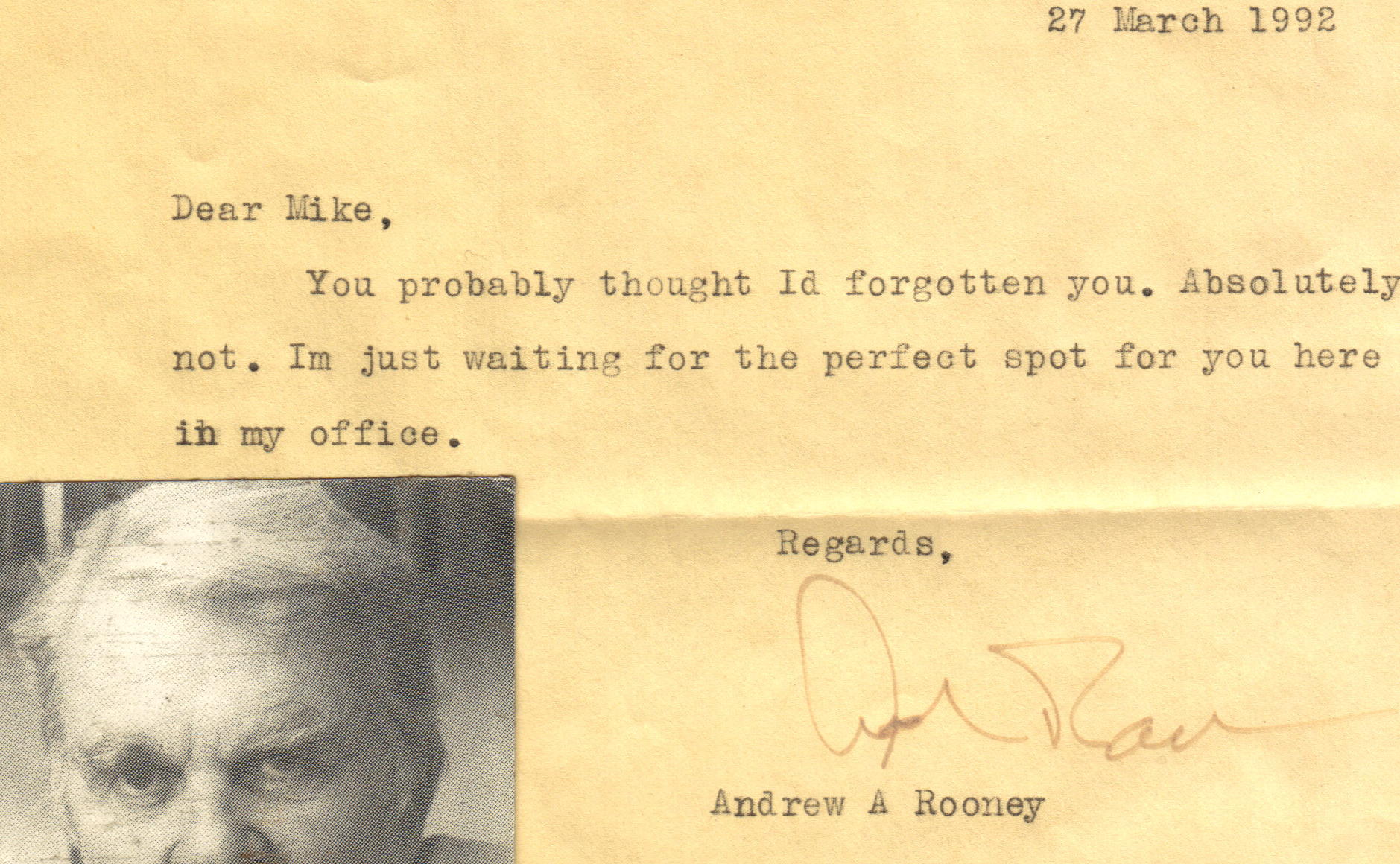

In another episode, Rooney jokingly asked if there was a viewer who could help him as a handyman/intern at work and around his house and I responded for the job, citing my newspaper articles on his behalf (while paying him for his columns) and the belief that he owed me. Rooney had long said that he never answered letters so I was thunderstruck when I got his lukewarm response (above) written on that famous mechanical typewriter.

Two years later I pulled one of Rooney‘s columns about Native Americans that was just stupidly wrong. The following week I published Rooney‘s apology where he admitted his stupidity/insensitivity/ignorance while correcting much of his F-troop history and assumptions.

The following week I got a Letter to the Editor demanding that I not publish anything more from Rooney “…or else!” But I responded with a several page editorial that I thought was thoughtful while addressing all issues. I never got another hate letter after that.

Andy was a life-long liberal who wrote much about the excess and foolishness of other leftists. He admitted that there was liberal bias in northeast media; he lampooned the direction some feminists were taking the woman’s-rights movement; he was an early critic of some political correctness disguised as doctrinaire agenda; he was baffled by Gen-Zero and its comparison to the Depression Era/World War Two generation. His opinions on War had evolved and could be at odds with many in his newsroom.

Had Rooney not retired he may have lived longer, still sticking pins in the right and the left. He may have softened up enough to give me a call with tickets to New York City and my new life as the personal squire to the last angry man.

Or, as Rooney would have said, “Don’t you hate it when people say nice things about you after you’re dead.”

Posted by Mike Cartel